If you were a newcomer to Mumbai, of all the places you might choose to stay, would Dharavi ever cross your mind? While the rents are high, accommodation here would burn a smaller hole in your pocket than in bohemian Bandra or neighbouring Sion. Does the word "slum" scare people away from renting a flat in Dharavi, or is it the lack of amenities? Where will I eat? Is there a toilet in the house? If not, how far away is a community or public toilet? Are spaces in Dharavi safe? Dharavi may be known as a slum, but it is home to lakhs of people in Mumbai - place for them to feel safe, uninhibited and comfortable to indulge in oneself in natural actions that are considered part of living.

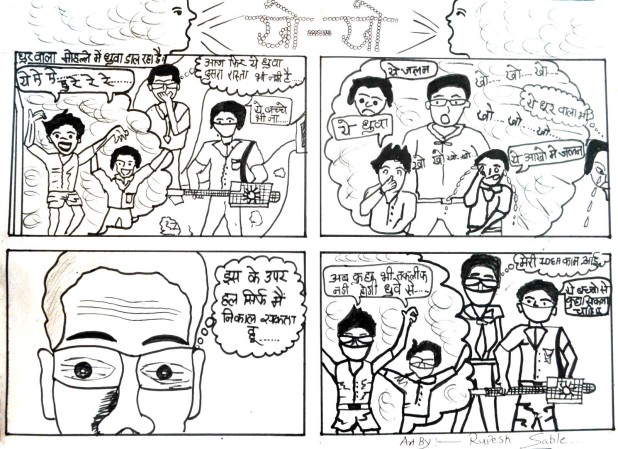

Manish Sharma, filmmaker and thoroughbred Delhi-walla, said that he was staying at our centre, the Colour Box, for almost a fortnight. He and his crew were making a movie - "Indefensible Spaces" - about toilets and women's safety in Dharavi. I met up with him to learn more about his experience and he said that he mainly chose to stay at the Colour Box because of accessibility. "We were filming in the nights and early mornings, the times when most Dharavi residents need to use the community toilets. I had an option of staying in Borivali, but that is the other end of town and much time would admittedly be wasted in commuting."

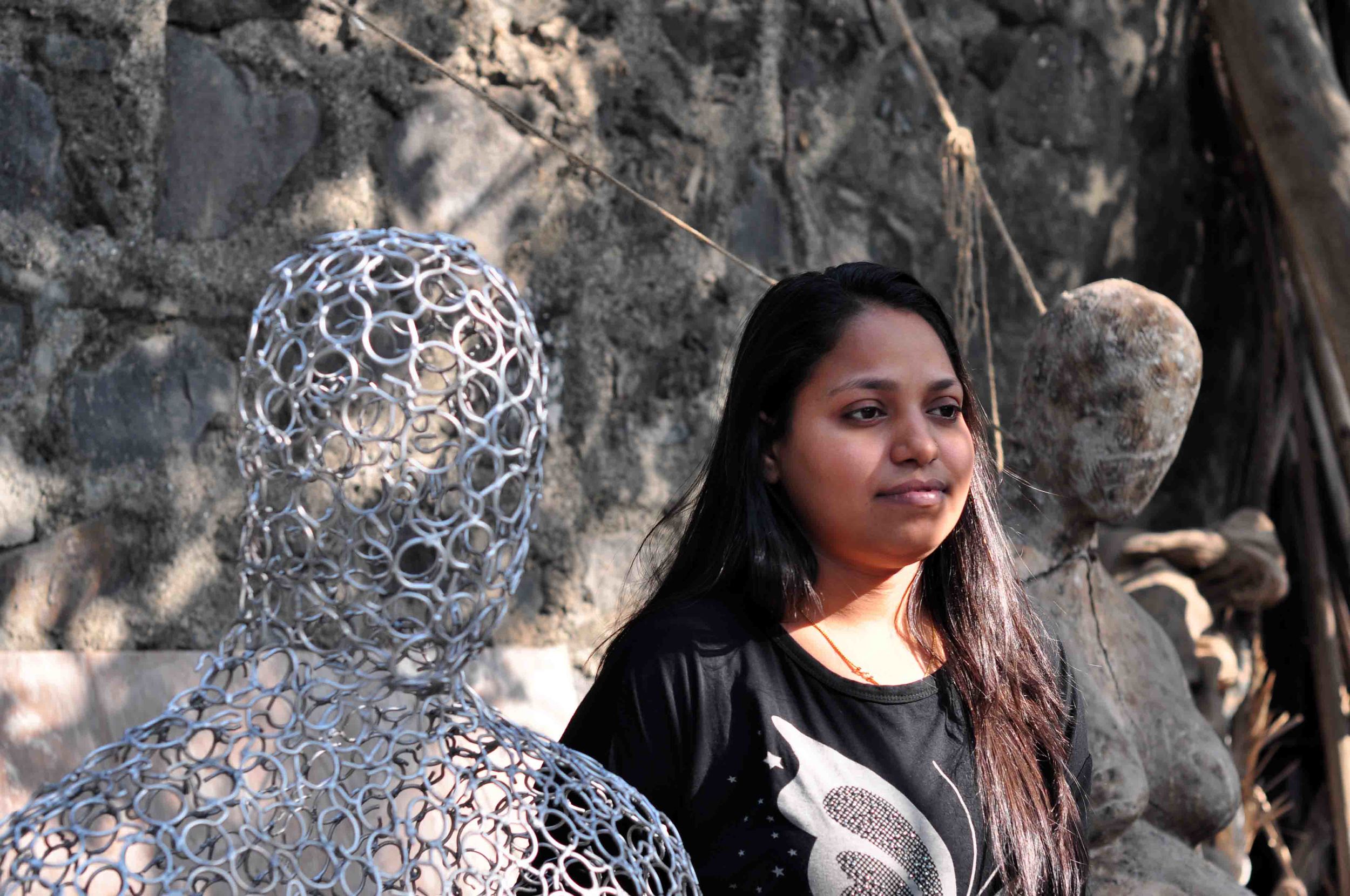

I wanted to ask Manish how he found his Dharavi stay as an "outsider". A number of slum tourism enterprises operate in Dharavi, and we have seen numerous foreigners on tours. But "foreigners" and "tourists" in Dharavi need not be from another country; they could be other Mumbaikars who may have driven through 60 Feet Road but never set foot in it. The Dharavi tourist is bound to be met with contrasting opinions - poor conditions available for human existence versus intense commercial activity. Opinions are easy, but living is difficult.

On the issue of safety, Manish hesitated to respond and then burst out laughing, "I must admit that on the first three days I was scared. We had equipment that was worth lakhs, including lenses and a Max, at the Colour Box. In the nights I was paranoid that someone might murder me and loot the place! I was a tad nervous about who might be keeping note of my comings and goings, especially looking at some of the drug addicts who frequent the neighbourhood in the nights." Even so, perhaps it is not unusual to have the jitters in a new place, especially if you are from New Delhi, which recorded a crime rate four times higher than Mumbai last year. "Of course, by the fourth night I had made friends with most people around and I even wished the druggies good night! I slept like a log on all nights after that with three coolers for company. There was this little mouse that crept over me one night, but I couldn't care less. My biggest trouble was sleeping on a mat and waking up in the mornings with straw marks on my face," continued Manish. At this point Rohin, his DoP, and I laughed and called him an elitist.

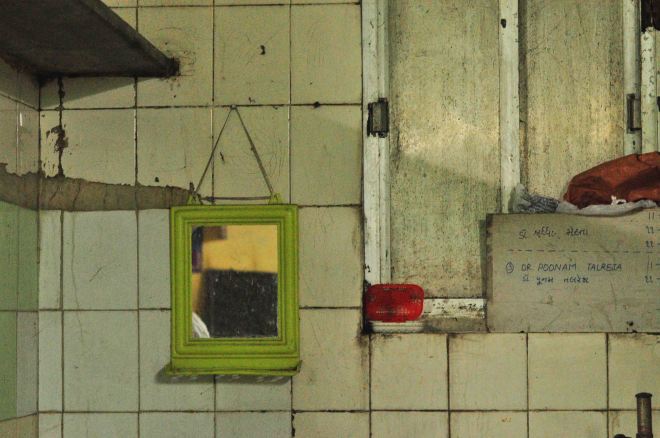

Manish was in Dharavi to make a film about toilets and we dipped our toes in the subject of his experience of toilets in Dharavi. "Space and time in Dharavi community toilets are luxuries. The days when I was here in Dharavi, I had to use public toilets and I must admit that I was too ashamed to in the beginning. The very fact that I had to reveal to a stranger that I had to sh*t was an embarrassment. Furthermore, standing in line and paying a couple of bucks to use what you think is a basic amenity in homes changed my perspective on things that we take for granted. If you like spending some twenty minutes in a loo, that is not what you will get in a common toilet. You feel a social responsibility to finish your job fast and let the others in line have their turn.

"It took me the first couple of days to get used to the idea of using a common toilet. Initially, I would just ignore any urge to pee and wait till I went to restaurants, like a pizza outlet in Sion, and guess what… they too didn't have toilets! I would then go to a cafe, order a dessert unnecessarily, stock up on calories and then use the loo there. Or I would travel all the way to a mall a couple of kilometres from Dharavi just for the sake of a pee!

"Every morning we set off to film people's morning routines near the toilets. It was an interesting scenario: women were carrying heavy buckets of water and looked very busy, whereas men looked like they were sitting around. I remembered what I was taught in school: that men have more muscle power to do heavy work. But what was baffling to see was that women were doing the heavy work and men did not seem to be helping them out. Watching this helped me understand what Dharavi mornings are all about and how gender roles get defined on the pretext of the woman being expected to be the caretaker of her home."

While Manish was filming with us, there was a rumour going about that he hadn't taken a bath on one of the days. I asked him if this was true and also assured him that it wasn't a big deal at all. He confirmed that he hadn't and said, "Well, you must be aware that we didn't have water in my initial days at Colour Box. This may have to be a secret. I took a bath under the tap in the boys' hostel in Chota Sion Hospital. I would walk from Colour Box to the Hospital with my toiletries. The hostel boys there either cared too much or didn't care who I was at all, and hence I bathed there till water was restored at Colour Box. In fact it is to be noted that while we have common toilets there is no concept of common bathrooms."

So, let us consider this: What does it take to call something your "home"? A toilet, a bathroom, water and electricity, but most of all, courage and familiarity with the space. Thus, do residences, such as those in Dharavi, qualify as homes if one has to pay access to a public toilet in the absence of a private one? If there is no water supply in your house for a major part of the day, is it still a livable space?

As mentor for a participatory film, Manish concluded, "An unexpected outcome of my stay was that the community participants found me more accessible. Some of the ladies called me over home for dinner, and they thought I was like one of them. Not just some camera-toting tourist who has come to make a movie on their lives."